What If AI Composed for Mr. S?

S氏がもしAI作曲家に代作させていたとしたら

Artificial Intelligence Art and Aesthetics Research Group (AIAARG)

人工知能美学芸術研究会(AI美芸研)

22 July – 7 October, 2019

Opening night reception with + publication launch: 22 July , 19:30 – 21:30

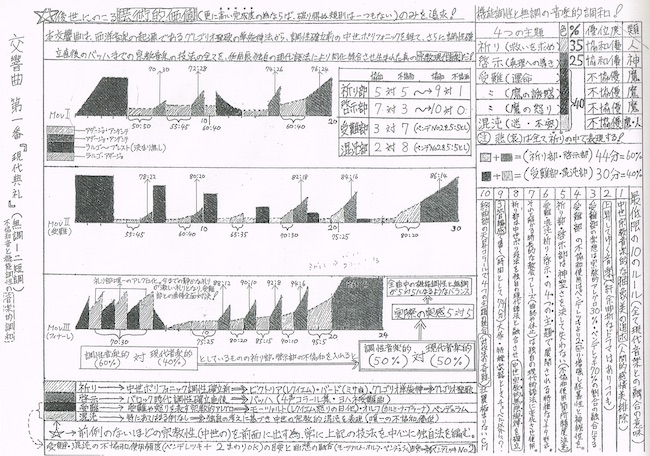

Copy of the instructions for Symphony No.1 “Hiroshima”, written by Mr. Samuragochi for Mr. Niigaki

|

然れば真実とは何であろうか? それは、隠喩、換喩、擬人化表現の動的な 一群、つまり、詩的かつ修辞的に際立たされ転用され潤色された人間関係 の総和である。それは、長く使われることによって、固定され、規範的で、拘束 力のあるものと人々に思われるようになった。真実とは、それが錯覚である ことが忘れられてしまった錯覚、使い古されて感覚的な力を失くしてしまっ た隠喩、肖像が消えてしまって最早コインではなく単なる金屑とみなされる ようになったコインなのである。

.

—「非モラルな感覚での真実と虚偽について」フリードリヒ·ニーチェ(1873)より

「S氏がもしAI作曲家に代作させていたとしたら」は、人工知能とそれが芸術創造の美学へ与える現在的または未来的影響についての展覧会であるはずだった。しかし最終的には、真実と倫理性、そして公衆(「傍観者」)の芸術創造の過程への役割へと主題が変わってきたのである。 2014年2月、著名な日本人クラシック作曲家である佐村河内守が、1996年以来、自身の作品とされていた音楽のいずれも作曲していなかった事実が浮上したとき、日本と国際メディアは荒れ狂った。音楽家と作曲家に東京の桐朋学園大学音楽学部の講師であった新垣隆を、佐村河内氏が「ゴーストライター」として雇い、新垣氏が20年近くも佐村河内氏の代理で作曲していたことが明らかにされた。神秘的雰囲気や世界最高の作曲家の一人であるベートーヴェンとの類似性を普及させるために佐村河内氏が何年も主張していた全聾も、まるで追い討ちをかけられるように、事実でなかったことも判明した。 佐村河内氏は4歳でピアノを弾き始め、現代日本の誇りと栄誉を代表する一人として名声を得て、また、海外メディアからは「デジタル時代のベートーヴェン」とも評されていた。最も讃えられたのは彼の交響曲第1番『HIROSHIMA(ヒロシマ)』(2003年)であり、2008年同地で開催されたG8サミットを記念するため初めて公に演奏された他、2014年ソチ開催の冬季オリンピックでは日本人フィギュアスケーターの高橋大輔選手にも使われるはずであった。 ニーチェは1873年に書かれたエッセイ「非モラルな感覚の内の真実と虚偽」で、我々が現実を露わにしたり隠すため、いかに言語を操るかを分析し、人間が全ての概念や隠喩を生み続ける最中、我々が「真実」の構築とその現実への関連性をしばしば忘れがちであることを主張した。然れば真実は、人間の知へ対する渇望が、帰属感を求める本能に際立たせられた、言語の行使に過ぎないことであると、ニーチェは暗に伝えている。我々は社会として、「真実」を言語に制定された、何らかの社会契約として扱うが、社会による真実の探求の動機は、欺騙ではなく、むしろ欺かれた時の感傷や不快のことでなかろうか。そうであれば、佐村河内氏は詐欺師なのであろうか?彼はただ、我々の感情を傷つけただけではないだろうか? ゴーストライターは、出版業界ではとても一般的に見られ、容認されている現象であり、通常では社会や批評家に社会的不快や感傷を引き起こさない。これは他のクリエイティブな営みにも当てはめられないものなのであろうか?芸術創造の分野でもまたとても容認可能な行為である。今日では、芸術家が作品を捏造し、あらゆる資源や過程を用いてアイディアを出すことはとても頻繁になっている。例えば、広告やメディアからインスピレーションを受けたり、刺激と影響のために他の芸術家の作品に依拠し、実際の捏造には工場や機械、パソコン3Dプリンターや職人を使うことが上がる。過去数年間では、ジェフ·クーンズなど今を生きる最も著名な芸術家でさえ、盗作の法的クレームを五つ以上も受けている(いくつかは法廷外で解決していても負けることもあり、一番最近な敗北は2018年である)。ところが、このような批判は、彼が1986年に作り、多大な影響力を持った彫刻作品、「ラビット(ウサギ)」をクリスティーズ·オークションで9,100万ドル以上で売ることも止めていない。佐村河内氏が左遷と恥の生活を送っている反面、クーンズは生きた芸術家による作品売却では最高額を収めた賞を軽くさらっていくのである。 誰かに作品を作ってもらうことも、全く新しいことでもない。数多くの古典的な大物芸術家も、我々が彼らの作品だと評するものに、アシスタントや弟子を雇っていたことが、密に記録されている。ミケランジェロが絵筆を持ち、はしごに登って、苦心して天井を描いていなかったとは言え、システィーナ礼拝堂を見下す者はいない。我々はやはりヴァチカンに群がり、彼の素晴らしい傑作と才能を評価するのである。 コンセプチュアル·アートの芸術家である中ザワヒデキと草刈ミカに率いられる、自由な集体である、日本のAI美芸研(人工知能美学芸術研究会)が、この展覧会のコンセプトを持ちかけた時、私は一瞬にして興味をそそられた。2016年に発足した当会は、AI技術がアート·プロダクションと美学に対して与えてきたインパクトと将来的に与え得るインパクトを研究するために立ち上げられた。彼らの初めてのメジャーな展覧会は沖縄科学技術大学院大学(OIST)によって主催され、人工知能の使用によって哲学的に方向付けられ、インスピレーションを受け、造られた作品が展覧された。アプローチは自由で柔軟で、AI技術そのものよりも哲学的なディスコースに大きく依存している。 AI美芸研は自分たちのコンセプトを哲学的な仮説として私に紹介し、佐村河内氏の「ゴースト作曲家」が生きた人間ではなくAIのソフトウェアであったならば社会の反応はどうであったか、という問いを見つめるものであった。盗用された彼の音楽作品の純真性へ対する見解を変えたであろうか?より重要な問いとして、タイプ1文明(カルダシェフ·スケールに夜)に急速に進化し、生物学的な身体がデジタル·技術的機械化と部分的に統合されるとも予測されている我々の世界において、芸術の創造と美学の未来について何を予見しているのであろうか? 答えはマルセル·デゥシャンの「クリエイティブ·アクト」(1957年)のエッセイ/講義にあるかもしれない。デゥシャンは芸術を創造する行為が、芸術家とクリエイターに、傍観者(または「後者」)と作品を体験する人々を、二つの「極」としたダイアログであると説いた。芸術の社会的価値観は、芸術家の努力や分析によって定義されるのではなく、むしろ社会の反応によって定義されると示唆した。つまり、我々が集体として、どんな芸術が「善い」のか価値があるのかを決めているのだ。 ザ·コンテナーでの「S氏がもしAI作曲家に代作させていたとしたら」の展覧会は、社会が佐村河内事件について再考し、芸術創造と美学の価値の未来について沈思する機会を与える。

シャイ・オハヨン |

What then is truth? A movable host of metaphors, metonymies, and anthropomorphisms: in short, a sum of human relation which have been poetically and rhetorically intensified, transferred, and embellished, and which, after long usage, seem to a people to be fixed, canonical, and binding. Truths are illusions which we have forgotten are illusions — they are metaphors that have become worn out and have been drained of sensuous force, coins which have lost their embossing and are now considered as metal and no longer as coins.

— From On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense by Friedrich Nietzsche, 1873

What if AI composed for Mr. S? intended to be an exhibition about Artificial Intelligence and the impact it may have, now or in the future, on the production or the aesthetics of art-making; but, in the end, the exhibition evolved to be about truth and morality, and the public’s (“the spectator”) role in the process of art creation. Japanese and international press ran amok in February 2014 with the revelation that the renowned Japanese classical composer, Mamoru Samuragochi, did not in fact wrote any of the music attributed to him since 1996. Instead, it was disclosed, Mr. Samuragochi deployed a “ghostwriter”, Takashi Niigaki, a musician, composer and a lecturer at Tokyo’s Toho Gakuen School of Music, who had been composing on his behalf for nearly two decades. To add injury to insult, it was also revealed that Samuragochi is not deaf, as he has been claiming for years, to perpetuate mystique and parallels to one of the world’s greatest composers, Beethoven. Mr. Samuragochi, who started to play the piano at the age of four, was one of modern Japan’s pride and glory, and was dubbed by foreign media as “digital-era Beethoven”. Most celebrated was his No. 1 Symphony “Hiroshima” (2003), which was first publicly played to commemorate the G8 meeting Hiroshima in 2008, and was due to be used by the Japanese figure skater Daisuke Takahashi at the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. Nietzsche in his essay from 1873 “On Truth and Lies in a Nonmoral Sense”, examines how we use language to reveal and conceal reality, and argues that as humans invent all concepts and metaphors, we tend to forget our role in constructing “truth” and its correspondence to reality. Truth, then, Nietzsche implies, is a language exercise, deriving from humans’ desire for knowledge, and enhanced by our basic instinct for belonging. As a society, we designate “truth” as some sort of a social contract, legislated by language. Society’s search for truth is not about deception, but rather the feeling of harm and unpleasantness when defrauded. Is Mr. Samuragochi really a fraud then, or did he just hurt our feelings? Ghostwriters are a very common and accepted phenomenon in the publishing industry, and usually do not trigger any social unpleasantness and hurt by the public or critics; but, can’t this be prescribed also to other creative processes? In art-making it is also a very acceptable practice. Nowadays, it is extremely common for artists to fabricate their works or deploy ideas using a range of resources and processes — taking inspiration from advertising and media, or relying on other artists’ works for stimulus and influence — while using factories, machines, computers, 3D printers or craftsmen for the actual fabrication. In the last few years, for example, one of the most acclaimed living artists, Jeff Koons, has been lodged with no less than five legal complains of plagiarism (some he lost, the latest in 2018, while some he settled out of court); nevertheless, it hasn’t stopped him from selling just last May his seminal sculpture from 1986, Rabbit, for over $91M at a Christie’s auction, scooping the accolade for the highest sum for any artwork by a living artist in history. So why has Mr. Samuragochi been propelled to live in exile and shame? Getting someone else to make your artwork for you is nothing new either. It is well documented that many of our classical master artists hired assistants and apprentices to do much of the works we attribute to them. No-one sniffs at the Sistine Chapel, even though Michelangelo wasn’t there on a ladder with a paintbrush painstakingly painting the ceiling. We still flock to the Vatican and credit him for his amazing masterpiece and talent. When the Japanese loose collective AIAARG (Artificial Intelligence Art and Aesthetics Research Group), headed by the conceptual artist Hideki Nakazawa and Mika Kusakari, discussed with me the concept for this exhibition, I was immediately intrigued. The collective was formed in 2016 to examine the impact AI technologies have, or may have in the future, on art production and aesthetics. Their first major exhibition was hosted by the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology University (OIST), and included works that were created, inspired, or philosophically driven by the use of Artificial Intelligence. Their approach is broad and flexible, and relies heavily on philosophical discourse rather than actual AI technologies. AIAARG introduced their concept to me as a philosophical hypothesis, contemplating what would be the public reaction if Samuragochi’s ghost-composer were to be an AI software and not a living person. Would that change the perception about the authenticity of his plagiarized music compositions? More importantly, what does it foresee for the future of art production and aesthetics as we rapidly progress into a Type 1 civilization (based on Kardashev scale), where our biological bodies are predicted to evolve to be partially integrated with digital / technological mechanization? The answer may hide in Marcel Duchamp’s essay / lecture from 1957 “The Creative Act” where he argues that the act of making art is consisting of a dialogue between the two “poles” — the artist, the creator, and the spectator (or the “posterity”), the people who experience the work. Duchamp suggests that the social value of art is defined not by the efforts or analysis of the artist, but rather by public reception. We, as a collective, decide what is “good” or valued. The exhibition at The Container What if AI composed for Mr. S? gives the public an opportunity to reinvestigate the case of Samuragochi, and to ponder on the future of art production and the value of aesthetics.

Shai Ohayon |