Defiance and Decadence Under Apartheid

アパルトヘイト下の抵抗と堕落

Billy Monk | ビリー・モンク

21 October, 2019 – 6 January, 2020

Opening night reception and publication launch: 21 October, 19:30 – 21:30

Publication

+

Screening of the documentary A Shot in the Dark (2019) and QA with the director / custodian of the Billy Monk Collection, Craig Cameron-Mackintosh: 25 October, 20:30-22:00 (RSVP essential)

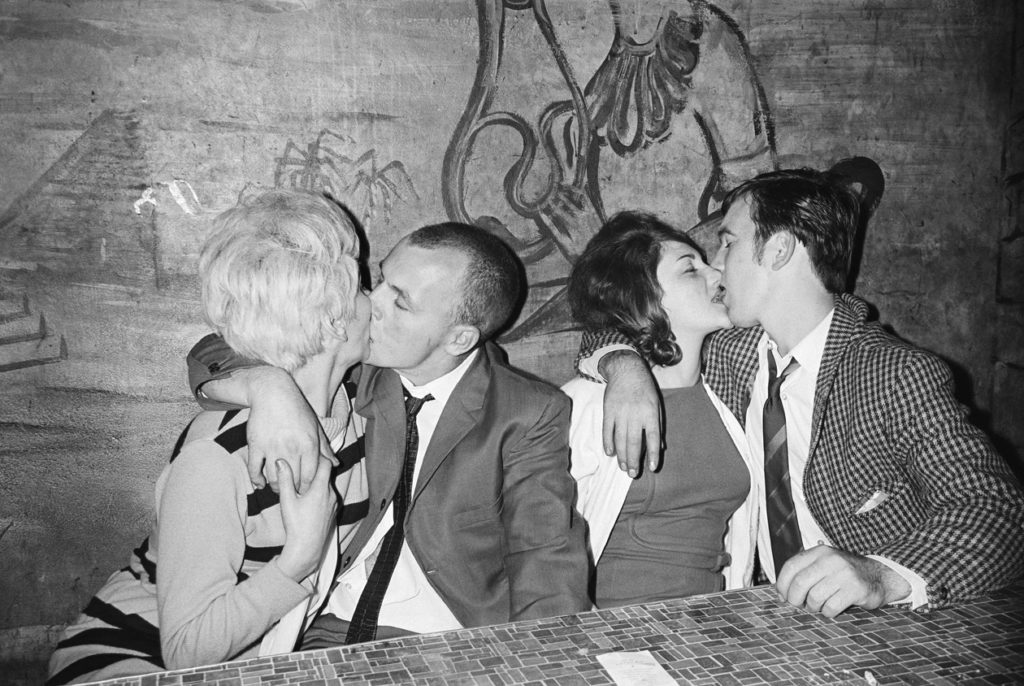

Billy Monk. The Catacombs, 1967. Courtesy of Billy Monk Collection.

|

南アフリカ人の写真家ビリー・モンクの作品は、まず彼自身のことについて語らなければならない。彼の謎めいた不思議な人生については多くのことが言われ、書かれてきた。怪しい取引や日和見的な仕事の多々。その淫乱さや、どんな道楽や違法行為に対しても強欲的とも言えるほど抱えた情熱。人懐っこい性質に良いルックス。それでもって、愉快でアプローチしやすい人柄。全ては南アフリカのアパルトヘイト時代の最盛期におけるケープタウンの裏社会の道楽者たちを捉えた、彼の美しくて完璧に造られた、粗々しい白黒写真にとって最重要で不可欠な要素であろう。 ビリー・モンクは何事もチャンスと捉えた。レストラン経営、モデル、ザリガニ密漁、密輸業、軽犯罪、ダイヤの潜水採掘。短期ながらもケープタウンの裏社会有数のナイトクラブ、ザ・カタコンベのバウンサーなど、様々な職に就いた。手っ取り早く金稼ぎができるものは、すぐに食らいついた。つまり周囲の人々にとってのモンクは、彼の全てを受け入れるか、完全に避けるかといった人物であった。モンクやモンクのことを知る者も、彼について何かしらの面白い話を知っていた。自身も語りが得意で、その興味深い話や詩的な談話は、聞き手を大きく魅了した。皆に愛されるか厭われるか、もしくは正体が掴めない、そんな男であった(モンクの正しい生年月日は確証されておらず、彼も子供時代のことについて語ることは淡々と避けていた)。 写真家としてのモンクのキャリアも、彼の人生の他の事と同様、単なる偶然に過ぎないようであった。彼を「悪いバウンサー」だと評していたカタコンベのクラブオーナーにとっては幸いなことに、バウンサーの仕事に飽きた彼は、ペンタックスカメラと35ミリフィルム、そして写真家のアシスタントとして働いた少しの経験だけを武器に、ナイトクラブの騒がしい客らを撮り、記念写真を売ることにしたのであった。しかし、全ての良い物語がそうであるように、万物は偶然ではないのである。モンクは道楽者たちの親密さと魅惑を捉える紛れもない能力を持ち、誘惑、喜び、カリスマ性あふれる喚情的な写真を生み出していった。 モンクの技術力もなかなかのものであった。暗い空間で小さなフラッシュを手に、三脚なしで撮影するという、決して理想的な環境で仕事できていなかったにも関わらず、奥行き深く、複雑かつ洗練された構成の繊細な写真を生むことに成功していた。しかしながら、彼の写真でそれ以上に鮮明なのは、被写体との間で育んだ親密で自然な関係性である。どの写真を取っても、モンクはただ記録をする部外者として撮影していたのではなく、自身も写真の一部であったことが明らかである。被写体らは利用されていたり、ぎこちない様子も示しておらず、心地よく、愉快に自由を祝っている様子である。モンクに撮られることを嬉しそうにし、撮影という営みに対して、写真家自身と同じくらいに積極的に参加している。 美的価値とコンテキスト双方の面で深遠な画像である。マーティン・ファーとジェリー・バッジャーは「ザ・フォトブック:歴史、第3巻」の導入で、モンクの作品の気骨や荒々しさと弱者の表象が、著名な日本人写真家、森山大道の白黒写真と雰囲気が似ていると分析している。 両者は似た美学的ビジュアル・テイストを有し、更にサブカルチャーを記録する上では、現代生活を象徴する分裂的な社会的本質に着眼するという共通の関心もあった。モンクの明瞭な写真はアパルトヘイト時代の日常生活で記録の上に多大な美的価値を包含する、唯一の画像なのかもしれない。美学的にも芸術的に同じくらい、歴史的に重要である。 モンクはプロの写真家としても、芸術家としても自らを宣伝することはなかったが、自身の写真の質と品位には薄々感づいていた。「なあ、俺はいつか写真で成功するはずさ。俺がいなくなって長く経った後、写真も話題になるさ。」とある友人に話した。彼は間違ってはいなかったが、同業の友人に保存目的で託した写真やネガ、詳細なメモが残ったスタジオに写真家のジャック・デ・ヴィリアーズが引っ越すまでは、10年以上の時間を要した。その頃にはモンクも写真に対する大志を忘れ、ダイヤモンドの潜水採掘者として前進し、比較的な成功も納め、金儲けもできる別キャリアを形成していた。 南アフリカ人写真家の故アンドリュー・メインティーズと故デイビッド・ゴールドブラットの助けを得て、ジャック・デ・ヴィリアーズは1982年にヨハネスブルクのマーケット・ギャラリーでビリー・モンクの写真にとって初となる展覧会を開いた。展覧会は批評家と公衆からの受けが良く、高評価も得た。モンクはオープニング・ナイトには出席できず、写真が受けた好評も知らなかったが、展覧されることだけへの興奮を胸に、オープニング何週間後に新しいスーツを購入してヨハネスブルクに向かった。モンクの人生はサプライズと思わぬ展開だらけだったが、ギャラリーに向かう途中、ある男と喧嘩になり、友人を守ろうとしたところ、銃殺されてしまった。至近距離で殺され、ギャラリーにたどり着くことはなかった。 1967年から1969年までのわずかな時間にモンクが写真家としてカタコンベで写真を撮った作品は国際的評価と写真史上で名声を得ている。作品はケープタウンのイジコ南アフリカ・ナショナル・ギャラリーやサンフランシスコ現代美術館、ニューヨークの国際写真センターで展示された。イジコ・ナショナル・ギャラリーとサンフランシスコ現代美術館、ヨハネスブルク・アート・ギャラリーはモンクの写真を永久コレクションに加え、モンクの作品と重要性を記す多数の本や記事も出版されている。最近では国際芸術祭にも現れ始めていて、そこでも温かく迎えられている。彼の人生についてのドキュメンタリー「ビリー・モンク ショット・イン・ザ・ダーク」(2019年。訳注:サブタイトルは掛け言葉であり、邦訳では「暗闇を写して」または「暗闇で撃たれて」とされる)もリリースされたばかりで、数々の国際映画祭でフィーチャーされている。 ザ・コンテナーでの「アパルトヘイト下での抵抗と堕落」はビリー・モンクの作品をアジアで初めて展覧する機会だ(香港でもパートナーのブギー・ウギー・フォトグラフィと共に同じ展覧会をフィーチャー済)。写真のセレクションはとてもユニークである。写真はそれぞれ1982年のマーケット・ギャラリーで展覧されたオリジナル・シリーズのもの、2019年の新たなビリー・モンク・コレクションのもの、世界中で初めてショーケースされるものの、三種類から成る。 セレクションはアジアのギャラリー客向けに選出されていて、カタコンベの多種多様な客入りを垣間見えさせる、ケープタウンを頻繁に訪れた日本人と香港人の船乗りやアジアの観光客の写真を多く紹介する。自身の肌色や、ゲイ、トランスジェンダーの女性、売春婦、道楽者など、不評判な社会的集団と関わりがあるだけで行動が制限された、南アフリカのアパルトヘイト時代において本当のサブカルチャーがどのようなものであったかを知る貴重な機会である。多様な人々が肩をもみあわせ、どんなことも許され、誰もがウェルカムだった寛容な社会空間が創られていたことを、モンクの写真は全て写し出している。いわゆる典型的な日本人サラリーマンが夜遅くのカラオケに手を伸ばして現地の女性と抱き合っている様子や、山手線の終電時の電車かのようにベンチの上で酔いつぶれている様子を、取り散らかった写真の混沌の中に見つけるのも実に滑稽だ。 「アパルトヘイト下での抵抗と堕落」では私たちは抑圧下の間にあった至福のひとときを垣間見ることができると同時に、既知のこともまた教え込まれるのである。それはつまり、人間の魂に愛と寛容は、どんな権力によって敷かれた差別的規則や制限よりも、強いということを。 |

It is impossible to write about the work of South African photographer, Billy Monk, without talking about the man himself. Much has been said and written about his mysterious and compelling life: his dodgy dealings, his sundry odd opportunistic jobs, his promiscuousness and ravenous enthusiasm for all forms of debauchery and law defiance, his affable character, his good looks, and most importantly, his convivial and approachable nature—are all as important as inseparable from his beautiful, perfectly composed, grainy black and white photographs of revelers in the underground scene of Cape Town, at the peak of the apartheid rule in South Africa.

Billy Monk was a chancer. He was a restauranteur, a model, a crayfish poacher, smuggler, petty criminal, diamond diver, and for a short while, a bouncer at Cape Town’s notorious underground nightclub The Catacombs. If there was a quick buck to be made, Monk would be there. He was a man to be reckoned with, or totally avoided, and it seems that everyone knew him, or of him, or had a good story to tell about him. He was also a man of many stories himself, captivating his audiences with charming tales and poetic anecdotes. He was the man that everyone loved, or hated, knew all or nothing about (even his actual birth date is not confirmed, as he smoothly avoided talking about his childhood). His career as a photographer, like everything else in his life, was seemingly nothing more than a coincidence. Bored of his work as a bouncer at The Catacombs, to the relief of the club owner, who describes him as a “bad bouncer”, Monk armed himself with a Pentax camera, 35mm film and a little technical experience from his stint as a photographer’s assistant, to photograph bacchants at the nightclub so he could sell the photographs as mementos. But like in all good tales, nothing is really a coincidence—Monk possessed an undeniable ability to capture the revelers with intimacy and allure, producing evocative images full of seductiveness, joy and charisma. Monk’s technical skills proved to be quite impressive. Despite taking the photographs in less than ideal conditions—in dark environments with nothing more than a small hand-flash and without a tripod—he still managed to produce sensitive photographs rich in depth and with complex and sophisticated compositions. More than that, as is most evident in his photographs, is the intimate and natural relationship he forged with his subjects. It is clear Monk was part of each and every photograph he took and not just an outsider who is documenting. The subjects seem comfortable, joyful and celebrating freedom, without a sign of exploitation or contrivance. They are happy to be photographed by Monk, and are as active participants in the process as the photographer himself. The images are profound both for their aesthetic value and for their context. In The Photobook: A History, Volume III, Martin Parr and Gerry Badger observe in their introduction about Monk’s work that his photographs share in their grittiness, roughness and portrayal of marginal characters a similar feel with the black and white photographs of the Japanese iconic photographer Daidō Moriyama. Both photographers possess a mutual visual artistic taste with an additional common interest in documenting subcultures, and in directing the focus on the socially fractional and disjointed nature that typifies modern life. Monk’s revealing photographs are perhaps the only images we have of apartheid-era’s everyday life that boast in addition to mere documentation also a significant artistic value. They are as important historically as they are aesthetically and artistically. While Monk did not market himself as a professional photographer or as an artist, he did have an inkling of the quality and integrity of his photographs. “You’ll see,” he said to a friend, “I’ll make it in photography. They’ll be talking about my photographs long after I’ve gone.” He was not wrong, but it would take another decade before the photographs were to be rediscovered by the photographer Jac de Villiers, after he moved into a studio where Monk left his photographs, negatives, and meticulous notes for safekeeping with a photographer friend. By then, Monk’s photography aspirations were long gone, and he had moved on, as he would, to forge a relatively successful and lucrative career as a diamond diver. With the help of the late South African photographers Andrew Meintjes and David Goldblatt, Jac de Villiers mounted the first exhibition of Billy Monk’s photographs at the Market Gallery in Johannesburg in 1982. The exhibition was well received by both critics and public, and was highly praised. Monk, unaware of the acclaim his photographs achieved, but excited nonetheless to have them exhibited, did not make the opening night, but he purchased a new suit and headed to Johannesburg a couple of weeks later to see the exhibition. However, Monk’s life was never short of surprises and twists, and sadly, on his way to the gallery he had an altercation with another man, while trying to protect a friend, and was shot dead. He was murdered at point-blank range and never made it to the exhibition. Since, Billy Monk’s works from his short spell as a photographer between 1967-1969, taking photographs at The Catacombs, did reach international acclaim and stature in photography history. His work was exhibited at the Iziko South African National Gallery in Cape Town, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and at the International Center of Photography in New York. The Iziko National Gallery, SFMoMA, and the Johannesburg Art Gallery also added Monk’s photographs to their permanent collections, while a number of books and dozens of published articles cite Monk’s works and their significance. Recently, Monk’s photographs also started to make appearances in international art fairs, to a warm reception, and a newly produced documentary about his life, “Billy Monk – Shot in the Dark”, has just been released (2019) and has featured at a number of international film festivals. Defiance and Decadence Under Apartheid, the exhibition of Billy Monk at The Container, launches for the first time the photographer’s works in Asia (we have featured the same exhibition also in Hong Kong, with our partners Boogie Woogie Photography). The selection of photographs for this exhibition is unique: some are from the original series presented in 1982 at the Market Gallery, some are from a newer series shown in 2019 by the Billy Monk Collection, and some, are showcased for the very first time—images that have never been exhibited before anywhere in the world. The selection is tailored specifically to Asian audiences and introduces also some images of Japanese and Hong Kongese sailors and Asian tourists who frequented the port of Cape Town, that give insight to the varied and multifarious crowd at The Catacombs. It is a rare opportunity to see what real-life subculture looked like in South Africa during the apartheid era, where individuals were restricted not only for their skin colour, but also for affiliation with other unpopular social groups, such as gays, transgender women, prostitutes, and late night revelers. In Monk’s photographs we can find them all—rubbing shoulders with one another and creating a permissive social bubble, where everything is acceptable and everyone is welcome. It is perhaps ironic to identify in the clutter and disarray the archetypical Japanese salarymen, suited and booted, taking to a bit of late night karaoke, in an embrace with local women, or just passed out on a bench, as if it were the last train on the Yamanote line. Defiance and Decadence Under Apartheid offers a glimpse of moments of happiness under oppression, and teaches us what we know already—that human spirit, love and acceptance are stronger than any discriminatory rules or restrictions imposed by any governing authorities. |