「トムに寄せて」

An Ode to Tom

三島剛 | 田亀源五郎 | 児雷也

Goh Mishima | Gengoroh Tagame | Jiraiya

21 September – 30 November, 2020

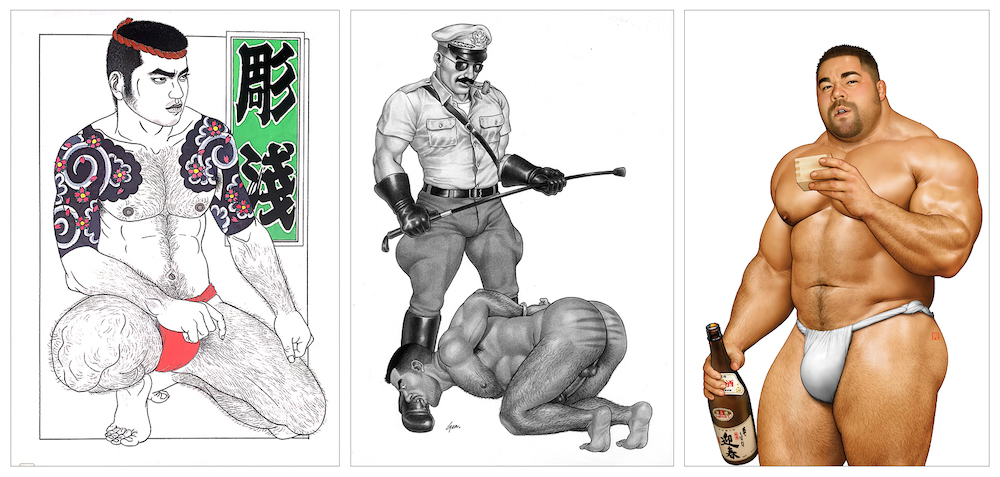

l-r: Untitled, Goh Mishima, Date unknown. Brush, pen, ink, paint, 282 x 380 mm; 無条件降伏 (“Unconditional Surrender”), Gengoroh Tagame, 1996. Pencil and alcohol marker; GG20-01, Jiraiya, January 2020. Digital illustration.

.

|

AAトム·オブ·フィンランド(Tom of Finland)財団の理事長、ダーク·デヘナー(Durk Dehner)と彼のチームと何ヶ月間にも及ぶやり取りとビデオ会議を重ねた末、私はようやく、彼らと面談するために「トムズ·ハウス」へ出向くこととなった。「トムズ·ハウス(Tom’s House)」は財団事務所に、トムに捧げられた博物館、一部財団員らの住居を兼ねている。その日の朝のロサンジェルスは、晴れて暖かな天候だった。太陽も明るく照っていて、私は東京からのフライトで何となく時差ぼけしていたが、胸を弾ませていた。

.

AA到着後、ダークとチームが案内してくれたダイニングルームは、おばあさんとゲイポルノ男優の装飾センスが混じった雰囲気としか説明できないような部屋だった。重厚なテーブルは古典的な可愛らしさを醸した椅子に囲まれ、ペニスやマッスル·ボーイの置物で飾られていた。財団員の一部メンバーはズボン、ブーツなど、上下全身のコーデをレザーでキメていた。それも火曜日の朝にだ。ゲイの美学はなんて普遍的なんだろうかと、私は感心が止まなかった。ヨーロッパ、アメリカ、アジア -ゲイ·クラブやカフェ- ここなんか、何の変哲もないダイニング·ルームだ。何かしらの美学さえが、その場所と環境を統一させているのであれば、どこにいようが関係ないのだ。 AAトム·オブ·フィンランドの作品イメージは、まさにこういったハイパー·マスキュリンな環境や描写と同義である。誇張された筋肉に隆々たるペニス、肉欲溢れる目線。ホモセクシュアリティの全てがこれというわけではないが、トムの作品が作り上げたビジュアルや、彼に影響を受けて生まれたファッション -例えば、カストロ·クローン、警察官、全身革コーデのバイカー、ヴィレッジ·ピープル、遍在的なヒゲともみあげ- 何をとっても、全部がゲイ、いや、「この上なくゲイ」なのだ。 AAトム·オブ·フィンランドの作品と、彼がLGBTQの権利のために精力的に取り組んだ活動は、何世代の人にインスピレーションを与えている。彼がアメリカやヨーロッパに対して与えた影響やアウェアネス(認識)を称えるのは容易だが、それ以外の地域にも影響力を及ぼしていたことを改めて指摘しなければならない。ここ日本でも、多くの芸術家やLGBTQの人々が彼と彼の作品の影響を受けてきた。 AAホモセクシュアリティとその芸術的表現に対する日本の態度は少し複雑で、様々な文化的要素が重なり合っているので重層的だが、従来からこうあったというわけではない。欧米ではここ半世紀の間、ホモセクシュアリティに対して徐々に寛容となってLGBTQの人々が社会に受け入れられてきたが、日本はその正反対の道を歩んでいたかのようだ。江戸時代では一般的な慣習として容認されてきたのが、今では風変わりで社会的に相応しくない生き方としてみられるようになってしまった(ここ十年においては多少の進歩もあったが)。 AA現代以前(明治時代終わりまで)の日本では、男性の同性愛関係は「男色」と呼ばれていた。しかし20世紀に入って西洋化が進むと、西洋的な性科学の思想が政治と社会に普及、浸透し、「男色」は徐々に抑制され、容認されなくなった。一時期は反社会的な行為とみなされ、違法(ソドミー扱い)とまでされてしまった。僧侶の隠遁生活、歌舞伎、男娼など、それまで広く容認されてきた男性同士の関係が象徴してきた、何百年に渡る「寛容な」歴史はもはや昔のもの、タブーな存在となってしまったのだ。 AAそれまで広く愛されてきた、ホモエロティック·ホモセクシュアルな芸術(多くは木版印刷)も同じ最期を迎えた。しかしながら、20世紀半ば頃からは、ビリー·ワードやトム·オブ·フィンランドなど、欧米諸国の先駆的なホモエロティックな芸術家に影響され、日本でも新たな世代の芸術家が徐々に台頭してきた。彼らは欧米の同輩からインスピレーションを受け、日本文化にふさわしいニュアンスを反映させながら、自分たちの美学や思想に基づいた作品を生んだ。 AAこの度ザ·コンテナーが開催する「トムに寄せて(An Ode to Tom)」展は、元々ダーク·デヘナーとの会話をきっかけに企画された展示である。現代日本の美術におけるホモセクシュアリティの表現で中心的な存在を務めてきた日本人ホモエロティック·アーティスト、三島剛、田亀源五郎、児雷也の三人のの作品を展示している。三人は共にトム·オブ·フィンランドのイメージや政治活動にインスピレーションを受けたと明言しており、二世代に渡る日本人ホモエロティック·アーティストたちを代表している。

AA三島剛(1924-1988)は現代日本でゲイ·アーティストが台頭した時期の中心人物の一人だった(田亀源五郎の解説によると)。トム·オブ·フィンランドのように、三島も成人になったばかりの時を軍隊で過ごし、初めての同性愛経験も従軍最中でのことだった。軍で過ごした時間は彼の男性の肉体美と男らしさへの関心を深め、後の彼の美学を形成した。また、彼は、1950年代後半にトム·オブ·フィンランドの作品を発見し、同氏の影響を直に受けた。 AA三島の初期の作品は、スポーツマンらしい男性のイラストがほとんどで、角刈りと刺青が多いのも特徴的だ。刺青に対する関心はヤクザへの興味から来たのかもしれない。当時のヤクザは、東京のゲイ·エリアこと、新宿二丁目で、数多くのゲイ·バーやクラブを経営していた。この頃の作品は総じてさっぱりとしていて、性的に誇張された描写が加わった伝統美術的なヌード·アートが彷彿される。全裸や男性器の露出はほとんど見受けられない。 AA親友だった三島由紀夫が死んだ後の晩期の作品は、陰気なものが多くなり、緊縛や拷問の描写が増えていった。男性器の描写も頻繁となり、アグレッシブでポルノ的要素が強くなった。本展では三島の作風をバランスよく、初期と晩期双方の作品を展示する。

AA田亀源五郎(1964生まれ)は、日本で最も有名で国際的にも著名な現代ゲイ·アーティストである。漫画家としての名声に加え、日本のホモエロティック·アートの学者、美術史家、ライター、記録人としても知られている。今回展示している三島の作品のほとんどは、田亀が個人コレクションから快く貸してくれたものだ(トム·オブ·フィンランド財団が提供した一つの作品を除いて)。 AA田亀の作品では、彼のフェチシズムへの関心が色濃く表現されており、特にサドマゾヒズム、拷問、緊縛など自身が創り上げた空想世界に根差した、現実離れした美観が特徴的だ。フェチシズムへの関心は、幼少期から青年時代にかけて、自身の性的指向に気付き、受け止めた頃に確立された。独特なアート·スタイルと興味分野は多摩美(多摩美術大学)から卒業して海外を飛び回った経験から深まった。海外に出たことで自身の性的視野も広がったが、装飾や宗教など様々な美的要素との出会いは、後の美観の発展に核心的な役を担った。 AA田亀の芸術的、活動家的な思想は90年代半ば、日本のホモセクシュアリティに対する保守的な態度が、ゲイ·カルチャーやLGBTQに関する知識の欠如に由来していることに気づいたことで発展した。これによって彼は、自身の芸術家としての立場を再考するようになり、正真正銘の現代日本人ゲイ·アーティストとして自分の役割を再定義すると同時に、LGBTQに関する問題がより広く注目され、社会認識が向上するよう、政治活動にも努めた。漫画家としての芸術的業績に加え、田亀の政治的及び学術的な貢献は、日本のLGBTQが近年遂げた進歩に必要不可欠だった。田亀はホモセクシュアリティの話題について現代日本で最もオープンであり、発言力がある人のうちの一人であり、LGBTQの認識と受け入れに向けての社会運動に欠かせない存在だ。作品もここ15年間では、国際的な舞台での展示や出版によって、世界的に認識され影響を及ぼすものとなり、日本でもNHKから取材依頼を受けるほど知られ渡るようになった。 AA本展では田亀のあらゆる側面や、今までに受けてきた影響を探求する作品のセレクションを展示する。さっぱりして、洗練されたピンアップの鉛筆·アクリル画や、銀次郎が繊細に描かれたペン·インク画。フェチシズムの生々しい描写、妖怪が生きた男の内臓を食べる様子を描いた、神話由来の作品「生き肝」など(「生き肝」とは、精力をつけるために生きた人間の内臓を食べる行為で、元々は中国神話に伝わる)。

AA最後に、本展では舞台裏での活躍者こと、イラストレーター·ゲイ漫画家の児雷也のデジタル画を複数展示する。本展で扱う芸術家の作品中では最も遊び心が溢れていて、日本のLGBTQコミュニティのより明るく愉快な側面を表現している。日本人の「ビーフケーキ」やカップル(日本語ではいわゆる大柄、筋骨隆々な男を「ガチムチ」と呼ぶ)を描いた作品が多く、日本の伝統的な装身具や装備を伴うものも多い。物憂げさを全面的に出した、田亀や三島のイメージとは対照的に、茶目っ気で面白楽しい雰囲気の作品が多い。 AA児雷也のゲイ·カルチャーとの出会いは、20代の時にゲイ雑誌「サブ」を発見したのが、きっかけだった。田亀も若い頃に同誌の影響を受けており、80年代後半には自分の作品も頻繁に掲載されるようになった。正しく児雷也も田亀から大きな影響を受けたと指摘していて、後からトム·オブ·フィンランドにも影響されたようだ。しかしながら、ゲイ漫画家として作品を生み出すようになったのは、30代に突入した、90年代後半までのことではなかった。当時、田亀が表紙イラストレーターを務めていたゲイ·ライフスタイル誌「G-Men」で作品を発表するようになった後のことだった。2001年に田亀が同誌を降板すると、表紙イラストレーターを引き継ぎ、漫画を寄稿するようになった。 AA児雷也の作品は、自身とホモセクシュアリティとの関係性を反映している。表舞台に立つことを避ける同氏は、政治的·アクティビスト的な挑発を避け、酒、ロマンス、グループ·セックス、スポーツなど、ゲイのより社会的な側面に目線を向けている。ほとんどがCGで作成されたイラストは、生き生きとした男性が描かれていて、その親しみやすい、売りの良いキャラ性は、ファッションやブランドとのコラボレーションを通して海外にも普及するようになった。日本のLGBTQに関する認識を向上させる立場を自発的に取っていないが、アジア人男性を愛想良く、男らしく描いたことで、アジア人は女々しくて中性的だという欧米人の先入観を払拭する一助となった。また日本でも、現代ゲイ·ファッションとゲイの振る舞い方を多方面から方向付けた。

AAトム·オブ·フィンランドの作品がヨーロッパとアメリカのLGBTQライフスタイル、美学、諸権利に影響を持ったように、本展で取り上げる日本人ゲイ·ホモエロティック·アーティストたち三人も、日本のLGBTQに対する社会認識の向上と、社会的態度の変化に一方ならぬ貢献をしてきた。LGBTQの権利が認められるまでの道のりはまだ長いが、LGBTQが社会に受け入られ、平等が実現されることへの社会的変化は加速している。それを推進してきた変革者たちこそ三島、田亀、児雷也のことであり、彼らの芸術とたまわぬ努力が日本の次世代のゲイ社会にとって進歩をもたらしてきた偉業は、改めて称賛すべきだ。 AAザ·コンテナーは、芸術を通じて、社会的少数者の平等と権利の保護のための議論を推進し、社会にポジティブな変化をもたらせるよう、このようなプラットフォームを提供し、支援できることをとても嬉しく思う。 |

AAAAfter many months of correspondence and virtual meetings with Durk Dehner, president of the Tom of Finland Foundation, and his team, I was at last headed to meet face-to-face at Tom’s House—the office of the foundation, a museum dedicated to Tom, and a residence to some of the team who runs it. It was a mild and clear late morning in LA, the sun was bright and I was excited and still slightly jet lagged from my flight from Tokyo.

AAAI was welcomed by Durk and his team upon arrival into a dining room that is best described as a cross between my grandma’s and a gay porn star’s: heavy wooden table and chairs with old-school charm, decorated with dicks and muscle-boys. Some of the Foundation’s team members were cladded with full leather gear: trousers, boots and all, on a Tuesday morning, and all I kept thinking was how universal gay aesthetics is. You can be in Europe, America, or Asia, in a gay club, cafe, or indeed, a homely dining room, and it doesn’t really matter, as a particular aesthetic language binds all the locations and settings. AAAIt is the hypermasculinity-charged environments and depictions that became synonymous with Tom of Finland’s works—exaggerated muscles, enlarged penises, and a gaze full of lust. Of course, this is hardly what homosexuality is all about, but the visual language it has developed, the fashion it created and inspired: from the Castro-clone man, to the policeman and leather-cladded biker, to the village-people, and the ubiquitous mustache and sideburns—are all gay. “Very gay.” AAATom of Finland, his art, and his tireless activist work for the rights of LGBTQ people, have inspired a couple of generations. It is easy to credit him for impact and awareness in the US and Europe, but important to highlight that his reach was much wider, and even here, in Japan, artists and LGBTQ people were inspired by him and his works. AAAJapan’s attitude towards homosexuality and artistic depictions of such are a bit complex and culturally layered, but it wasn’t always this way. Unlike the west, which gradually experienced over the last 50 years more and more tolerance towards homosexuality and acceptance of LGBTQ people, Japan seemingly almost had gone in the opposite direction—from a commonplace and acceptable practice during the Edo period, to a more discreet and not so acceptable choice of living nowadays (although some positive progression has taken place during the last decade). AAANanshoku, a term used in Japan to refer to male-to-male sexual relationship in the pre modern era (up to the Meiji period), became less and less encouraged and acceptable with the westernization process of Japan during the twentieth century, and rendered even hostile and illegal (sodomy) at some point, as western ideas of sexology became more prevalent and adapted by Japanese lawmakers and society. An entire history of tolerance—represented in the popularity of male-to-male relationships in monastic settings, in Kabuki theatre, and in male prostitution—lasting many hundreds of years, fell out of fashion and became taboo. AAASo have the ubiquitous and beloved artistic depictions (mainly prints) of homosexual acts and homoerotic art. Nonetheless, with pioneering western homoerotic artists such as Bill Ward and Tom of Finland, a new generation of contemporary Japanese homoerotic artists has slowly started to emerge from mid twentieth century, taking inspiration from their western compeers, and producing works motivated by their aesthetic and ideological ideas, with a culturally appropriate Japanese overtone. AAAThe exhibition at The Container, An Ode to Tom, was initially roused by some conversations I had with Durk Dehner, and features artworks by three Japanese homoerotic artists that evolved to be pivotal in the representation of homosexuality in contemporary Japanese art: Goh Mishima, Gengoroh Tagame, and Jiraiya. All three artists have spoken openly in the past about drawing inspiration from Tom of Finland’s imagery and political activist works, and represent also two generations of homoerotic artists in Japan.

AAAGoh Mishima (1924-1988) was one of the central figures of the first wave of contemporary gay artists in Japan (as defined by Gengoroh Tagame’s art history reference). Similarly to Tom of Finland, he had started his adult life with a military career and had his first homosexual experiences in the military. His service in many ways defined his aesthetics and appreciation for the male body and masculinity, as well as direct influence from the works of Tom of Finland after he discovered his drawings in the late 50’s. AAAMishima’s earlier works are typified by illustration-like depictions of athletic men, often fashioning crewcut hairstyles and adorned by Japanese-styled tattoos (irezumi). Mishima’s interest with this style of tattoos may derive from his fascination with the yakuza, who coincidentally, also operated at the time many of the gay bars and clubs in Tokyo’s gay area, Shinjuku Ni-chome. The drawings are clean and reminiscent of classical artistic nudes, with added sexually-charged compositions. Most of them do not reveal the body in full or the genitals. AAALater works, following the death of his good friend Yukio Mishima, turned more morbid, where compositions of violence, shibari (Japanese bondage), and torture became more commonplace. These later drawings also featured genitals more frequently, and have a more aggressive and more pornographic nature. In the exhibition we are featuring both types of works to give a well-rounded insight into Mishima’s practice.

AAAGengoroh Tagame (1964-present) is Japan’s most celebrated and internationally renowned contemporary gay artist. In addition to his prolific practice as a manga artist, he is also a well respected academic, art historian, a published writer, and an archivist of Japanese homoerotic art. Indeed, most of the pieces by Mishima we are showcasing in this exhibition are kindly borrowed from Tagame’s private collection (with the exception of one, which we received from the collection of the Tom of Finland Foundation.) AAATagame’s works are characterized by his fascination with fetishism, in particular sadomasochism, torture, and bondage and an aesthetic sensibility that is detached from reality and rooted in a newly constructed fictional actuality. His interest in fetishism had evolved already in his childhood and teenage years, while realizing his sexual orientation and coming to terms with it. His particular style and interests had broadened after his graduation from “Tamabi” (Tama University of the Arts) and following extensive international travels, that enabled him not only to expand his personal sexual horizon, but also to be introduced to many types of decorative and religious art elements that found themselves influential in the aesthetic language that he developed. AAAMuch of Tagame’s artistic and activist ideology has matured in the mid 90’s with the realization that Japan’s conservative attitude towards homosexuality lacked any kind of representation of gay culture or LGBTQ awareness. This cognizance encouraged Tagame to reevaluate his own position as an artist and led him to redefine his role exclusively as a contemporary Japanese gay artist, hand-in-hand with political activism to bring attention and recognition to LGBTQ issues in Japan. His artistic contributions as a manga artist, as well as his activist work and academic work, are integral of the progress LGBTQ people have made in Japan in the last few decades. Tagame is one of the most open and vocal forces in Japan about homosexuality, and has been indispensable to contemporary efforts to bring awareness and acceptance to LGBTQ people. In the last 15 years Tagame’s work also became recognized and influential in the international arena with exhibitions and publications worldwide, and forced its way even into the mainstream in Japan, with commissions from the national broadcaster (NHK). AAAIn the exhibition at The Container we showcase a selection of works that explore the many faces and influences of Tagame’s works—from his pencil and acrylic clean and stylized pin ups, to the torturous pen and ink compositions of Ginjiroh, his graphic depictions of fetishism, and the mythology-inspired painting “Ikigimo”, showcasing yōkai (monsters) eating the organs of a living man (ikigimo is the Japanese term for the act of eating a living human’s liver in order to gain power, based on an old myth from China).

AAALastly, the exhibition also features a number of digital drawings of the reclusive Japanese illustrator and gay manga artist Jiraiya (1967-present). He is the most playful selection for this exhibition and represents a lighter and more joyful perspective of the Japanese LGBTQ community. His drawings usually portray Japanese beefcake pinups / couples (gachimuchi, a term used to describe chubby-muscular men), often fashioning traditional Japanese accessories or paraphernalia. They are frolicsome and merry, a high contrast to the loaded and dark imagery of Tagame and Mishima. AAAJiraiya was introduced to gay culture in his twenties, after discovering Japan’s gay magazine Sabu, the same magazine that inspired Tagame in his youth and by late 80’s featured his work heavily. Indeed, Jiraiya points out that he was profoundly influenced by Tagame’s work, and later, also by the works of Tom of Finland. His professional work, however, as a gay manga artist did not unfold till late 90’s, when he was already in his thirties, after publishing works in the Japanese gay lifestyle magazine G-Men, where Tagame served as the resident cover artist. By 2001, after Tagame’s retirement from the magazine, Jiraiya took over to become G-Men’s cover artist, as well as manga contributor. AAAJiraiya’s works reflect his personal relationship to homosexuality—closeted and reclusive he evades political or activist confrontations and focuses more on social aspects of gayness: drinking, romance, group sex, and playing sports. His, almost exclusively digital, illustrations of effervescent men have a commercial and affable quality which found their way also to clothing and brand collaborations worldwide. While he did not position himself to consciously create awareness to LGBTQ people in Japan, his joyous and masculine Asian men, helped to challenge the perception of the western notion that Asian men are effeminate and androgynous, and indeed, define in many ways, the fashion and demeanor of contemporary gay men in Japan.

AAASimilarly to the impact Tom of Finland’s works have made in Europe and the US on LGBTQ lifestyle, aesthetics, and rights, these selection of three Japanese homoerotic artists contributed to increased awareness and change of attitudes in Japan towards LGBTQ people. While much work still needs to be done to recognizing the rights of LGBTQ people in Japan, there is a slow and gradual social transformation that pushes for equality and acceptance. Mishima, Tagame, and Jiraiya are some of the catalysts that promoted these social changes, and are credited through their relentless artistic efforts to bring a change for the next generation of gay people in Japan. AAAThe Container is proud to give a platform to these efforts to make a positive change, and to create an opportunity for discourse in Japan, through artworks, for social equality and the rights and inclusion of social minorities. |