作品を描く方法 | How I paint some of my paintings

中村 穣二 | Joji Nakamura

27 February – 8 May, 2017

Opening night reception + launch of publication: 27 February, 19:30 – 21:30

|

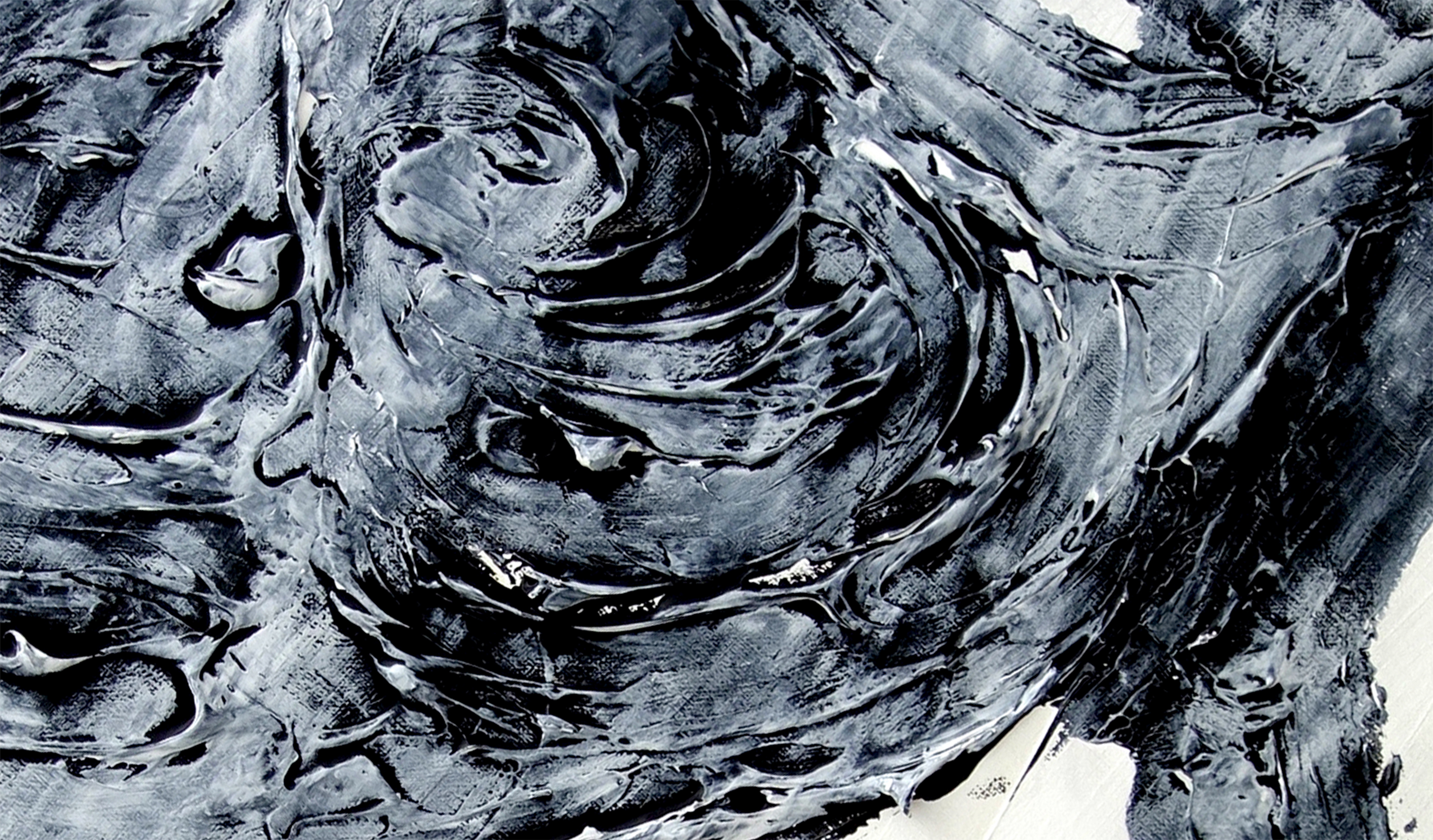

中村穣二は一人のアーティストです。「アートの場」を作らず、美術学校に通った事もなく、そして正直に言えば、美術史や背景への興味も持っていません。しかしそれでも中村はアーティストです。実際に中村は東京の最も理解されていないアーティストの中の一人に違いなく、上手く流行りと停滞を行き来する中で、現在に見られる最も素晴らしい日本人による抽象画を多数制作しています。そして、中村の団欒には年代で最も有名なアーティストが含まれる中でも、中村は用心深くアート・コミュニティーのメンバーではなく、只の友達としての立場を決めています。楽しみの為へと居るのです。 中村は自身をアーティストだと言うでしょう。その中の一人となる事を決めたのです。アートへの興味は、日本を離れカリフォルニア州のサンタバーバラに居住していた間に築いたアーティスト達との友人関係によって引き起こされました。彼らの作品や生活様式に影響を受けました。更に音楽への興味と、不良達との交流を含めたその他自由時間の追求と共に、それは中村の人生と信条へと完璧に適応していました。「アーティストとしての確立」を考えた事はなく、只一人と成りたかったのです。肩書きに付く政治やからくりを抜きに、唯一作品制作の為に。過程に携わる事です。 目にしてきたアート作品や出会った友達に影響され、日本への帰還と共に自分自身の作品を作り始めました。その作品は自発的であり、ペンや鉛筆とアクリル絵具による本能的なマークと、通常キャンバスや紙の表面との感情的な交流で特徴付けられています。その介在は素早くて偶発的、そして流動的です。絵具を使用する際には、筆を使わずに手だけを使用します。結果のイメージは激しく大胆であり、線には体積があり、意思表示の形状は密度があります。大半の作品は単色で、よく黒と白だけを時々青や赤等の追加色と利用しています。 中村の絵画を初めて目にした時、それらの作品は直ぐにジャクソン・ポロックの自発的な絵画方法や、ジャーン・ポール・リオペルの質感と、そしてロバート・マザウェルの構成等の、50年から60年代の抽象的表現主義を思い起こさせました。しかし、中村の作品により親しむごとに、その作品はダダ主義の反体制自動的抽象の表現に根付いている事に気付きました。資本階級への作品制作ではなく、制度と秩序の拒否。この認識が特に過程においての中村の作品を更に面白くさせました。どの位の期間で制作し、どの程度の時間がかかり、それを何処で作り、どの様にして変更するのでしょうか? The Container(コンテナ)の展覧会へと中村穣二を招待した後に、この展覧会では中村の制作過程への洞察を紹介するべき事が明確になりました。中村の「美術界」への参加に対する不本意な感情と自発的な技術は、何故中村はアーティストであり、そして新しい観念を確立させる新しい手段での観覧者への作品提供を理解する助けとなります。 The Containerでの展覧会How I paint some of my paintings(作品を描く方法)の合てる焦点は、中村の衝動的で直感的な作品制作の過程です。スペースの内部の壁は紙で覆われ、約177cmの高さと1,150cmの長さの引き続く表面を作り上げており、アーティストはその上へと、精神的な儀式にもよく似たプライベートなパフォーマンス形式で、1日を制作に費やしました。このパフォーマンスはビデオに収録され、中村の絵画と作品制作との個人的で親密な関係への洞察の提供、そしてアーティストとしての作品との感情的で物質的な関係を記録しています。 この展覧会で展示されている様々なサイズの用紙上へのアクリル画は、コンテナ内部でのアクション・パフォーマンス中に中村が主に制作した巨大な表面から選択された部分です。皮肉にも、中村にとってこの制作行為は計画的ではなく、変更は別の問題でした。中村はどう作品を切り取るかを丹念に熟慮し想定しました。決断を下す前に、構成とサイズを長く慎重に、異なる視点から視野を置いて思考しました。当作品の残りは処分され、スペースの床に投げ出されています。既に中村にとってこれらの必要性はないのです。 エンディングノートとして、東京のClear Editionギャラリーに対し、特に佐藤拓氏による本展覧会の準備への協力と援助へと感謝の言葉を述べたいと思います。 |

Joji Nakamura is an artist. He doesn’t do “the art scene,” he never went to art school, and quite honestly, he is not that interested in art theory or context. But he is an artist, nevertheless. In fact, he must be one of Tokyo’s most underappreciated artists—skillfully slithering on and off the radar—while prolifically producing some of the best Japanese abstract paintings currently available. And although his social circle includes some the best well-known artists of his generation, Nakamura carefully negotiates his position with them only as a friend, not as a member of the art community. He is only there for the laughs. Nakamura would tell you himself he’s an artist. He decided to become one. His interest in art was triggered by friendships he forged with artists while living away from Japan in Santa-Barbara, California. He was inspired by their works and by their lifestyle. It fitted perfectly with his life and beliefs, with his interest also in music, and his other leisure pursuits that consisted of hanging out with punks and skaters. He never really cared about “being an artist,” he just wanted to be one. Without the politics and mechanics attached to the title. Just for the sake of making art. Being engaged in the process. Upon Nakamura’s return to Japan he started to make his own art, inspired by artworks he has seen and friends he has made. The works are typified by spontaneous, emotional interactions with a surface—usually canvas or paper—instinctively marked with pen, pencil, or acrylic paints. The interventions are quick, unpremeditated, and fluid. When applying paints, he doesn’t use brushes—only his hands. The resulting images are fierce and confident, the lines have volume and the gestural shapes have body. Most of the works are monochromatic, often using only black and white, sometimes with an additional color, such as blue or red. When I saw Nakamura’s paintings for the first time, they immediately brought to mind abstract expressionist art of the 50s-60s: the spontaneous painting methods of Jackson Pollock, the textures of Jean Paul Riopelle, and the compositions of Robert Motherwell; however, as I became more familiar with his works I came to realize that they are rooted more in the antiestablishment automatic abstracts of the Dada movement. Not the creation of art for the bourgeois but a rejection of systems and orders. This realization made me more fascinated with his works, especially his processes. How does he make his pieces, how long do they take to make, where does he make them, how does he edit? After inviting Joji Nakamura to show at The Container, it became apparent to me that his exhibition must give an insight into the production process of his works. His reluctance to participate in “the artworld,” as much as his spontaneous techniques, are instrumental in understanding why he is an artist, as well as presenting his works in a new way that enables viewers to gain a new appreciation to them. The focus of the exhibition, How I paint some of my paintings, at The Container is Nakamura’s impulsive and intuitive process of art making. The interior walls of the space have been covered with paper, making a continuous surface that is approximately 177 cm tall by 1,150 cm long, on which the artist, in a private performance of some sort, akin to a spiritual ritual, spent a day painting. The performance, recorded on video, gives insight to Nakamura’s personal and intimate relationship with painting and art creation, and documents his emotional and physical connection to his work as an artist. The exhibited pieces in this show, acrylic paintings on paper in various sizes, are the selected segments taken from the large surface Nakamura initially painted during his action performance inside the container. Ironically, while the act of painting is so unpremeditated for Nakamura, editing is quite a different kettle of fish—Nakamura painstakingly considers and contemplates how to crop his works. He lingeringly deliberates on composition and size, tries viewing from different perspectives, before taking any decisions. The remainder of the painting is disposed of, discarded on the floor of the space. Nakamura has no use for it anymore. As an ending note, I would like also to thank Clear Edition gallery in Tokyo, in particular Taku Sato, for the cooperation and support in preparation for this exhibition.

|