Jack McLean

1 December 2014 – 15 February 2015

Opening night reception: 1 December, 19:30 – 21:30

+ Live performance art by the artist

+ Live music by Anthony Magor

.

| ジャック・マックレーンの作品にふれるということは、単に絵画を見るということではありません。それは、マックレーンの産み出した、不思議なファンタジーの世界を覗くということです。マックレーンが丁寧に思い描く不思議と驚きに満ちた世界は、奇妙なシナリオと人物達でいっぱいです。マックレーンの作品の登場人物は、まさに色とりどり。フィクションから歴史的人物、マックレーン自身が出会った印象的な人物が続々と登場してきます。 彼が絶えず持ち歩く、小さなスケッチブックは人のスケッチでいっぱいです。二十年前、 スコットランドに住んでいた頃の知り合いから、東京の込み合った電車ですれ違った人達。悪夢から蘇えったゾンビ、ヤンキー、肥満症の観光客、オカマ男からサラリーマンなど、様々な人物が見られます。マックレーンの豊かな創造力により、記憶と想像はスケッチへと変わり、 私たちの目の前に広がる絵画の中の世界が発現します。シリーズは全部で七つの絵画です。この七つの中で、繰り返し絵画に現れてくる人物が三人います。それは、マックレーンの過去の作品から引っ張りだされたイエッテー、彫像とピエロです。2008年から2010年の二年間を渡って、世界各地の公園で披露したコンセプシャル・パフォーマンスシリーズ ”Hole” に登場した、キャラクターが再び登場します。”Hole”に出演した、イエッテーの衣装を着たマックレーンが、今回の作品でも、木の陰に隠れたり、謎の穴を掘っていたりと、様々なシナリオで現れます。また、1995年から1996年の間に行われた、20年前の作品も引用されます。ライフサイズのアルミフォイルと針金で創られた彫像が世界中の観光スポット十カ所に送られ、放火されたパフォーマンス、”Pyrosculptures” の彫像もところどころで絵画に出現することがあります。そして、もちろんマックレーンの最新のキャラクター「悲しげなピエロ」も出番があります。 |

芸術家の作品は、芸術家自身の心の中を移す鏡とよく言われています。しかし、マックレーンの作品はそれ以上の役割を果たしています。作品に見られる、皮肉なユーモアとシュールレアリスムな奇行とは違い、落ち着いた気性を持つマックレーンはとてもプライベートな人です。 その為、彼に会うと、驚く人も少なくはありません。静かな口調と身に纏うダンディな1950年風のスリーピーススーツ。まさに昔式なジェントルマンを思い浮かばせるマックレーンは、芸術的偏心より、むしろ普通以上に保守的で昔風の価値観を抱いていそうな印象を与えます。彼の作品を拝見することは、彼の心の鏡に覗き込むのではありません。一心不乱に、彼の想像の中に存在する、不思議で少し悪夢のような国へ突っ込んでいくような体験です。彼の絵画は、新しい人物やナラチブの続きが、じっくり見れば見るほどあらわになります。それはまるで、人物がカンバスの上で生きていて、時間が経つにつれ、新しい冒険が書き続けられていく、終わりのない物語のように。マックレーンの作品は心の鏡というよりは、彼の頭の中に広がる、記憶と想像から生まれた世界への入り口のようなものなのではないでしょうか。

マックレーンの絵図には、奇妙な効果があります。ついつい、熱中してしまい、見ることをやめられなくなります。まるで、友達の子供のころのアルバムをこっそり見るかのような感覚におそわれます。面白くて、少し狂っている、マックレーンの作品は視聴者を時には笑わせ、時には心配させるでしょう。彼独特の、ブリティッシュユーモアで、一つ一つのシナリオはパロディで豊富です。ふざけていて、すこし乱暴なそのユーモアはまさに、イギリスの70年代、80年代の代表的なスラップステッキコメディ「モンティー・パイソン」などを思い浮かばせます。

今回のジャック・マックレーンが。「ざ・コンテインナー」にて展覧する絵画シリーズ”It’s a long sad story, in full colour, with an unhappy ending” は、今までの作品より遥かに、話法的な性質が窺えます。

展示会の主な焦点は、繋がっている三つの絵画です。「ザ・コンテインナー」のスペースを意識して、キャンバスがデザインされています。 “With full colour”と色使いをタイトルで主張していることから分かるかもしれませんが、マックレーンがカラーを使うことは滅多にありません。普段は、黒を愛用しているマックレーンにとって、今回は少し変わったシリーズです。子供が絵を描く時に使うような原色をもとに、純粋な子供らしさが思い浮かびます。無邪気で明るい描写方法と残酷なシナリオの比較により、一層不気味な印象を残すのでしょう。

「ザ・コンテインナー」に立ち入るとすぐに、視聴者は巻物のように壁を飾るキャンバス(9x450cm)にむかえられます。キャンバスの上で繰り広がるのは、「悲しげなピエロ」の生涯です。海からの誕生から、営み、そして最後に海へ戻る場面が描かれています。

「ザ・コンテインナー」の壁を飾る、細長のキャンバスはナラティブをコミックのように物語ります。静かな田舎を背景に始まるストーリーは、主人公のピエロへの変身と冒険を辿ります。主人公は、マックレーンがパフォーマンスで着用する、ピエロの衣装を纏い、ピエロのメイクをするに従い、着々とダークな人物に変わってきます。彼自身のメタモーフィスと同時に 静かな田舎道から、壊乱と暗黒な世界へと環境も変わってきます。爆撃、グロテスクな人物、射撃場や死にかけの赤ん坊を背景に、ピエロは無関心のまま、このキャンバス上に写るカオスな世界をさまよい続けます。最後のシーンでは、ピエロが誕生した海辺の背景へ戻りますが、海は鮫や水雷などで危ない場所へと変わっています。マックレーンの物語にはハッピーエンドはありません。

マックレーンが、絵画一つ一つに付けたタイトルは、異常に長く、明確に絵画に描かれている状況を説明します。「ザ・コンテインナー」の後ろ壁を覆っている絵画は、恐ろしい風景を背後にして、ピックニックを楽しむ若い家族が窺えます。この、絵画のタイトルは:

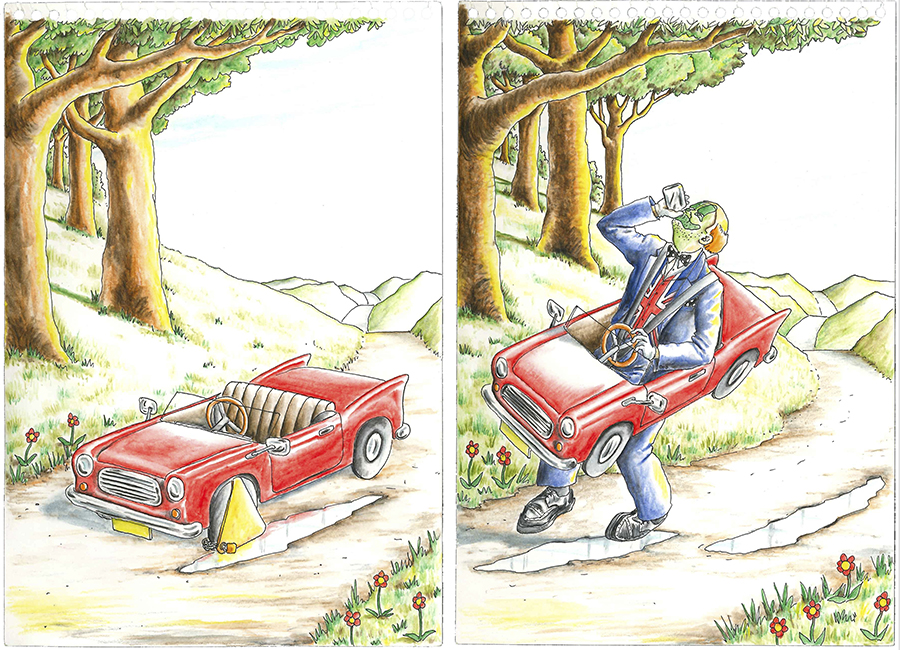

長閑な風景の中で平穏で幸せな家族ピックニックを楽しむはずだった山本家は突然謎の団体から爆撃されるところだが実はまた他の方向からは人食いゾンビに襲われそうになっているしかしそれには親とサッカー選手になることを無我夢中になっているから長男は気づかず一人の赤ん坊だけ気づいている家族に迫りつつある人食いゾンビの群れは実は家族を狙う前にオフィスを訪ねようとしていたということは二人の科学者にとってどうでもいいことでありそれより自分たちがどうすれば蓋を開けずにビールを楽しめることができるのかという問題に頭を悩ましている彼らはガスマスクを外しては原子力発電所から川に流れ込み空中に放された放射線や近くにある爆発した火山からの有毒なガスを含んだ空気を吸い込んでいることにもお構いなしであるが彼らとは違って世の中の現状に絶望感を抱く主人公のピエロは悲しみのあまりに酔っぱらいすぎて盗んだ赤いスポーツカーを橋に突撃しては瓦礫のなかから這いずりあがり彼の始めた意味のない絶望に満ちた世の中を進んで行く旅を続けると同時に死人の腐りかかった手足が再び動き始め誰も通りすがらない道すがりには悪い男に連れ去られた少年の赤い三輪車がポツンと置き忘れられている。

(ジャック・マックレーン、2014、オイルインクと水槽が水彩、133x178cm)

ナラチブは三つ目のキャンバスに続きます。また、ピエロの旅を辿り、今度は子供の海賊団、オカマな海兵、ハワイでバカンス中の肥満症な観光客、遭難したパイロット、KKK、チャールズ・マンソン、ヒットラーと人食い恐竜に出会います。イエス・キリストですら、危険から真逃れません。

絵画に描かれている最後のシーンは、ピエロが楽観的な表情で崖の上から紙飛行機を飛ばしている、いつもとは違う平凡なイメージです。しかし、ピエロが何気なく寄りかかっているスクーターは実は以前の絵画でピエロが子供を脅迫して手に入れたことを知っている視聴者は、暴力に普段関わらない人物ですら完全に悪害と無関係ではないことに気づきます。シリーズの最後でありながら、無解決なストーリーは視聴者にとって続きが気になるでしょう。

When one looks at a Jack McLean drawing, one doesn’t only look at a drawing: one sinks into a world of absurdity and fantasy, the way only, really, McLean knows to create. His scenes are carefully crafted and packed with an obscure narrative, full of characters and adventures of wonder. Some of the characters are real—figments of memory, vignettes, from his life in Glasgow, Scotland, some twenty years ago, or from his current life in Tokyo—and some are too surreal to have ever existed. Characters that were conceived on Tokyo’s train system, ones perhaps of thousands, amassing in McLean’s tiny sketchbooks, which he carries with him everywhere: zombies and tortured souls, hooligans and disfigured men, obese and hideous holidaymakers. Characters with multiple limbs, sometimes dressed in drag, or jaded salarymen and old familiar faces taken from popular culture.Most interesting is McLean’s perpetual references to his own works within his drawings: tiny self-portraits of himself donning his handmade ghillie suit, hiding among trees, or digging holes, as in his conceptual/performance series Hole (2008-2010), “a public sculptural intervention” as he calls it, instigated in Glasgow, Tokyo, London’s Regents Park, and New York’s Central Park; his Pyrosculptures (1995-1996), a series of life-size aluminum foil and wire figures he shipped in cardboard boxes to ten different cities around the world to be set alight at major tourist sites; and, of course, his Sad Clown, his performance persona, who is as hated as he is beloved, with his cringing awkwardness and helplessness. Standing alone, or with his performance troupe “Accumulated Sound of Idiocy”, a surreal band consisting of a nearly naked bodybuilder, flexing his muscles, an awkward Japanese man wearing a fez and fashioning a fake moustache, and the “beautiful assistant”, a female model in a bikini, who seems to be too high maintenance even for her own good.

They say that art is a window to an artist’s mind, but McLean’s works do more than that. Perhaps because his disposition is so controlled and private when one meets him in person. Softly spoken, immaculately dressed in 1950s three-piece suits, like a true gentleman from bygone times, McLean bestows an air of old-fashioned values, and I dare say, normality. There is no hint of the eccentricity that lies beneath—the dry humor, surreality, and sharp criticism. When looking at his works, one does not peek through a window; one drowns in a world that is so private and so imaginative, that once the overwhelming sensation subsides, wonder and surprise take over. His large drawings are so intense, one can spend hours in front each one of them, constantly discovering new characters, new story lines, in a cynical and morbid narrative, that never seems to ends. It does, indeed, feel like venturing into his head, getting lost in his grey matter, encountering flashes of people and long lost memories while wandering through a landscape.

This sensation makes his drawings strangely addictive, like looking at someone’s childhood photo album or rummaging through their drawers in secret. An insight into one’s head that is both exciting and worrying. We are lucky, though, McLean has such a good sense of humor, because looking at his drawings is as going on an adventure, with many giggles along the way. Not shy of mockery and ridiculousness, a doze or two of violence, and some naughtiness to finish off with. The humor is strongly reminiscent of 70s and 80s British comedy, dry and full of parody and cynicism, as you would find in slapstick shows such as “Carry On!”, “The Benny Hills Show”, “’Allo ‘Allo!”, or Monty Python. The narrative nature of Jack McLean’s drawings is stronger than ever in his new exhibition, It’s a long sad story, in full colour, without a happy ending, at The Container.

The main focus of the exhibition is three conjoined drawings, a triptych of sort, that take the viewer on an actual journey, both visually and physically. McLean designed the drawings as a site-specific installation, following the shape of the actual container. As the title suggests, the drawings for this show are in full colour, which is atypically for McLean who traditionally draws in black ink and black watercolour. However, the palette is not complex, using basic primary and secondary colours as perhaps a child would: the grass is green and the sky is blue, like illustrations in a children’s book. Alas, seeing McLean’s characters in colour for the first time, adds a new dimension to his drawings, as does a simplicity that emphasizes the naïveté of the drawings, and heightens the contrast between the childlike style and the unsettling imagery.

Upon entering the container, one is confronted with a scroll-like canvas (9 x 450 cm) that reaches the end of the space. The canvas takes the viewer on a venture, unfolding the life and exploits of the Sad Clown, from his “birth”, evolving from the sea (“the soup of nothing,” the title suggests), in a Darwinian-style drawing, to his end posture of loneliness and longing, perhaps foreshadowed by the erupting volcano in the distance, at the beginning.

The narrow and long canvas forces the viewer through the exhibition space, following the horizontal narrative like a comic strip or animation cells. The story, which begins in an idyll countryside scenery with grazing sheep and pink bunnies, sees the main character transforming into the Sad Clown, wearing the outfit McLean uses for his live performances—dark business suite, hand-painted Union Jack waistcoat, and polka dot tie. The transformation continues with the character applying army-issue camouflage makeup to paint a clown’s face. The metamorphosis into the Sad Clown brings also a change to the tranquil surroundings that quickly switch to a world of violence and corruption. Explosions overhead, grotesque characters, shooting soldiers, impaled babies, all whilst the clown plays a tune on his accordion or blows penis-shaped balloons. The world of absurdity continues from one scene to another encountering violence and destruction. The canvas ends with a tableau of the clown alone again, with his walking stick, on the shore of the sea, but the sharks, mines and looming iceberg, don’t augur a happy ending.

This elongated canvas meets at the end of the container an additional large drawing (133 x 175 cm) that continues the narrative and covers nearly the entire back wall of the space. At the centre of the canvas there is a young Japanese family at the park, enjoying their picnic (or, at least, trying to), whilst scenes of madness continue in the background.

The narrative continues with another elongated canvas (again, 9 x 450 cm) to complete the triptych. The new story line begins where it meets the second drawing, and will lead the viewer, back again, all the way up to the other end of the space, near the exit. The story, as expected, sees the Sad Clown through more adventures: a raft with children-pirates—the ship of fools, exceedingly camp sailors, obese tourists in Hawaii, and a deserted pilot, among gnomes, the KKK, Charles Manson, Hitler, and dinosaurs devouring dismembered limbs of people. Even Jesus is not spared.

The drawing ends again with a tableau of the Sad Clown, this time, at the edge of a cliff, looking towards the horizon in untypical optimism—flying a paper airplane. Though, we know already, that the scooter he is casually leaning on was obtained by theft and the intimidation of a child, with a bottle. It seems that even the Sad Clown, who is usually an unaffected observant of the violence around him, joins in. It is a cliffhanger ending that leaves the viewer (and by the title of the piece, also the Sad Clown) wondering what is next.